Ernest Hemingway is credited with saying, “The only kind of writing is rewriting,” although countless writers have expressed a variation on “Writing is rewriting.” While this conventional wisdom is solid, in screenwriting, continually doing a traditional Page-One Rewrite yields diminishing returns.

While I’ve offered up seven essential pointers for the polish and hone phase of rewriting, these innovative techniques that can boost your next draft, creating an impeccable script and an exceptional reading experience – key to impressing readers and advancing your career.

Rewriting is always work, but it comes with rich rewards. Adopting this new system can make the labor easier and produce more impressive results.

Press Pause

Congratulations! You did make it to “Fade Out.” But before you jump into a rewrite, step away. A little time off can yield big benefits. Set a time limit of a day or two so you have a plan in place, setting boundaries in advance.

After staring at the screen, writing, reading, and reworking, a break is an opportunity to refresh. Get out – of your workspace. Do an activity you enjoy, utterly unconnected to writing. Choose something active that doesn’t involve a lot of thinking but has a tangible result. Whatever floats your boat: baking bread, hiking to a scenic spot, working in the garden, or working out.

My favorite benefit of pressing pause is the phenomenon of “Sudden Illumination” – that spark of creativity that happens when we stop hunting for answers and instead to allow for the creative magic of the solutions that pop up when we stop seeking them.

So step back and take a not only well-deserved break, but an essential opportunity to refresh, re-energize, and let your subconscious take the wheel.

Press Print

I remember thinking I would never be able to write creatively on a computer. Now I can’t imagine how I survived writing on paper, with arrows and asterisks drawn all over the page whenever I discovered a better way to say something. Cut and paste – yes, please!

But rewriting is different.

I never post a column or a blog without printing it out. An astonishing amount of little errors slip by when reading on the computer. The inevitable better ideas can be scribbled in, and a couple of good old arrows and asterisks can move text around, then back to the computer to implement it. I can’t explain it, but there is something powerful about having words on paper and a pen in your hand.

This is a crucial aspect of the Just One Thing Rewrite, so please print. Don’t bother with three-hole punch paper – you’re not gonna need it. And that also means no brads necessary. Now you’re ready to work.

Scene-by–Scene

Solid scenes stand alone, as if they are a small story unto themselves. The best way to check is by reading one scene at a time – but not in order, or you’ll become caught up in the through line. The strongest scenes do two things at once – advance the plot and develop character.

Ask Yourself: Are you giving characters time to digest new information or shift emotional states? Is there a build in the big moments? Are you getting into the scene as late as possible? Does the scene build and end on a strong note? Can you wrap it up with a “bow” or a “button” – a great line and/or a meaningful action or reaction? If the scene was cut, would the screenplay still work? If so, it’s not essential. Does the scene add something new to the story? If not, then revise it or cut it.

Be on the Look Out For: Scenes that are filler. Expository scenes, transition scenes, and flashbacks are all scenes to consider trimming, revising, incorporating into other scenes, or cutting.

Dialogue Only

Each character should have a distinctive voice. By the time readers are in Act Two, we shouldn’t have to read the slug to know who is speaking. Read it aloud to hear the flow. If it’s awkward coming from your mouth, even a terrific actor won’t make it work. Great dialogue has a flow, a build, and a rhythm. See my ode to Aaron Sorkin as part of my discussion of “The Rule of Threes” in dialogue, along with many other terrific examples here.

Be on the Look Out For: Characters whose voices don’t remain consistent. There might be a distinctive cadence to their dialogue. If they use slang or have an accent at the outset, then they shouldn’t suddenly switch from “ain’t” to “shan’t,” or from “y’all” to “youse.”

Description Only

I’ve devoted entire ScriptMag articles to description, but here’s what you should focus on in the description-only pass:

- Are you giving us what is essential to know about the character when they are introduced? Is this something that can or will be conveyed cinematically?

- Are you conveying the atmosphere of significant settings? Just enough to give us the flavor.

- Is your detail too specific? Small details slow the pace. Unless they’re essential to conveying the atmosphere or establishing the character, we don’t need them. Leave the color of the shirt to the costume designer and the pile of the rug to the set designer.

- Are you telling us what we see as we see it? A character doesn’t flinch before the punch is thrown. Using “as” is a dead giveaway here.

- Do the sentences read smoothly? It should flow for the reader. Avoid lengthy sentences. Punctuate perfectly.

Ask Yourself: Are you using the same verb or adjective in close proximity? This signals weak writing and gives the piece a repetitive feel. Push yourself for variety, without going overboard.

Be on the Look Out For: More than three things in introducing a primary character or significant setting is giving us a grocery list, not a description. Avoid obsessing over small actions that our brains automatically fill in. Of course a character extends their arm to shake hands or turns the knob to exit through a door. Speaking of exiting, watch out for description that sounds like a play, such as having characters “enter” or “exit” a scene. It feels flat, not cinematic.

Backasswards

This may seem counterintuitive, but the backwards pass is a terrific tool because it pulls your focus to the look and the formatting. The last page is a terrific place to start. If it’s a half page long or less, now is the time to hunt down widows/orphans – lines with only one or two words – and rewrite the sentence so it is tighter. With strong word choices, you can say more with less and have greater impact for a better read. That’s the real goal. And, although less significant, you’ll also have a shorter page count.

Ask Yourself: Are there big blocks of dialogue or description? If so, what can be tightened and trimmed, or cut altogether. Is the page cluttered? As I said in “Five Things Readers Wish Every Writer Knew,” reading is literally hard on the eyes. We’re not asking you to make our job easier, just don’t make it more difficult. Keep it clean, clear and consistent. Scene numbers are for shooting scripts. If you have characters whose dialogue is in a language other than English, just above the first time it happens try this:

NOTE: Portuguese dialogue is in italics and will be subtitled.

I’m sure this will controversial, but I’m encouraging my consulting clients and the pro writers working on projects with me to eliminate unnecessary formatting, even if it means overriding the software. We really, truly do not need (CONT.), or (cont’d), (MORE) and CUT TO. Call the software company for help if you can’t figure out how. Keep parentheticals to a minimum and never use them in description – it’s either significant or it’s not. I also find characters exact ages in parentheticals to add annoying visual clutter. Unless significant to the plot, or in the case of kids from babies to teens, “thirties” will do fine and not limit casting. All CAPS for sound effects is outdated, but if you’ve got a particularly significant one, the BOOM of an explosion or the furious SLAM of a door that needs to land with impact, then have at it. Underlining or CAPPING for emphasis in dialogue adds clutter. It’s cleaner and every bit as impactful when italicized, just as it would be in a document. Honestly! Nevertheless, be judicious.

Be on the Look Out For: Inconsistent formatting. The spacing between lines and scenes can be thrown off in the best of programs. How you choose to convey the text of a sign or a jump in time should always look the same. No long slug lines. This is no place to convey the setting; that’s the job of description. Dashes and ellipses in dialogue are two different things. Dashes indicate a pause or hesitation, stuttering or sputtering, or being interrupted. Ellipses indicate trailing off, such as a character searching for what to say, and imply a longer pause. Lots of ellipses add a lot of clutter. Don’t be heavy-handed with either.

Just One More Thing

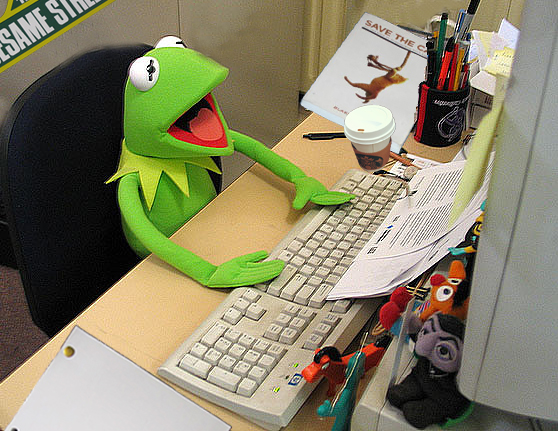

An experienced reader can – and will – pick up your script and be able tell in one to two minutes tops if you’re an accomplished writer or an aspiring amateur. One of my earliest ScriptMag articles, It’s Not Easy Being Green, shows you how to convince us you’re inexperienced, brought to you straight from Sesame Street!

Any of these rewriting techniques can elevate your writing, which is essential in impressing readers with your execution.

All of them are designed to trick your brain into seeing your words on the page with fresh eyes.

While a great consultant can catch these fumbles, practicing them with these rewriting strategies will train your brain to become aware of them as you write. Strengthening these muscles one at a time makes the heavy lifting easier with each script and every draft you do, as it becomes instinct instead of effort.